Executive Summary

Every day, people around the world make one of the most difficult decisions in their lives: to leave their homes in search of safety. These people are refugees – men, women, and children who cannot return to their own country because they are at risk of serious human rights violations there.

Under the administration of US President Donald Trump, the USA’s discriminatory and restrictive policies, starting with the Muslim ban signed in January 2017, have had a devastating impact on the lives of refugees everywhere. This impact is felt acutely in Lebanon, which hosts the largest number of refugees in the world relative to its size, and Jordan, which hosts the second largest refugee population in proportion to its national population. One in six people in Lebanon is a refugee registered with the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), while in Jordan, one in 14 people is a refugee.

Since 2017, the current US administration’s policies targeting refugees from Muslim-majority countries have decimated refugee resettlement from Jordan and Lebanon. Starting with the Muslim ban, and followed by successive refugee bans, cuts to refugee admissions, and extreme vetting, resettlement from both Jordan and Lebanon to the USA has plummeted and not recovered. UNHCR attributes a four-fold decrease in the resettlement of refugees from Jordan alone to the change in US policies.

Syrian refugee resettlement to the USA from Jordan and Lebanon has plummeted 94 percent in just over three years because of US policies targeting refugees from Muslim-majority countries. Ninety-nine percent of refugees in Lebanon are Syrian, while 87 percent of refugees in Jordan are. Yet, at the end of April 2019, only 219 Syrian refugees had arrived to the United States from Jordan and Lebanon this calendar year, putting the USA on pace to resettle just over 650 by the end of 2019. In contrast, in calendar year 2016, 11,204 Syrian refugees were resettled to the USA from Jordan and Lebanon.

But not only Syrians are impacted – resettlement to the USA from Jordan and Lebanon of Iraqis, Sudanese, and other nationalities from Muslim-majority countries has precipitously dropped due to the Muslim ban and the successive refugee bans and other policies hindering resettlement to the USA.

Read MoreWhen someone has to leave his country, he would feel heartbroken . . . We were obliged, we either die or save our lives and leave our country, so we chose to leave our country to protect our families.

Methodology

This briefing draws on 48 interviews Amnesty International conducted in November 2018 with refugee families and individuals registered with UNHCR and with the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestinian Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA). Amnesty International conducted some of the interviews in the refugee camps of Zaatari and Azraq in Jordan, and the Palestinian refugee camps of Shatila and Burj Barajneh in Lebanon. The organization also interviewed refugee protection professionals from UNHCR, UNRWA, international and national agencies, local refugee service providers, and community-based organizations in Jordan and Lebanon. Amnesty International has withheld names and other personal details of those who spoke to researchers for their privacy and security.

Amnesty International thanks all the women, men, and children who generously gave their time to share their experiences of displacement and life as refugees in Jordan and Lebanon. Amnesty International also thanks the advocates, refugee protection professionals, local refugee service providers, and community-based organizations who shared their expertise.

International Standards for Refugee Protection

The international community came together in a commitment of solidarity and legal protection for refugees through the 1951 UN Refugee Convention and its accompanying 1967 Protocol. The Refugee Convention defines a refugee as someone who “owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country.” The US Congress incorporated this definition into US immigration law in the Refugee Act of 1980.

Refugees have a right to international protection and fall under the mandate of UNHCR, which is charged with overseeing the implementation of the Refugee Convention. UNHCR pursues three durable solutions for refugees: voluntary return to countries of origin, local integration in host countries, or resettlement or relocation through alternative pathways to a third country. The resettlement process is normally coordinated by UNHCR, which identifies recognized refugees based on a set of vulnerability criteria and submits their cases to countries that have offered resettlement places who then decide whether to accept them for resettlement. If a resettlement country agrees to admit a refugee, it then actively facilitates the safe transport of refugees to and their integration in their country.

States have the power to control admissions by non-citizens to their territory within limits imposed by their obligations under international law. In particular, differences in treatment between different categories of non-citizens can only be justified under international human rights law if they are necessary to achieve a legitimate objective, including, among others, the protection of national security.

‘We Need Someone to Give Us Human Rights’: Palestinian Refugees in Lebanon and Jordan

Since US President Donald Trump took office in January 2017, US government policies have had a devastating impact on the lives of refugees in Jordan and Lebanon – particularly on Syrian and Palestinian refugees, including Palestinian refugees from Syria (PRS). Whether under the mandate of UNHCR or UNRWA, refugees in Lebanon and Jordan are part of one global ecosystem for international refugee protection, and the international community should address their needs holistically.

Just over five million of the world’s 25.4 million refugees are Palestinians. The majority live in Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, the Gaza Strip, and the West Bank. Palestinian refugees, both those who are long-term residents of Lebanon and Jordan and those who have fled from Syria, are excluded from UNHCR’s resettlement program because they are under UNRWA's mandate in its countries of operation. However, UNRWA has no authority to refer Palestinian refugees for resettlement to third countries, as this goes beyond its mandate of providing humanitarian assistance, including access to primary health care and primary education, housing assistance, and emergency food aid.

We depend on UNRWA. UNRWA can’t be replaced. NGOs can’t take the role of UNRWA because it provides services for all Palestinians.

Approximately 450,000 Palestinian refugees are registered with UNRWA in Lebanon and reside in formal and informal camps. Although the majority were born in the country and have lived there all their lives, they cannot acquire Lebanese nationality, and many remain stateless and deprived of access to public services including medical care and education. Discriminatory laws bar Palestinians from practicing over 30 professions, including medicine, dentistry, law, architecture, and engineering. Such restrictions have trapped many Palestinian refugees in deprivation and poverty.

We need someone to give us human rights. We need our rights, especially in Lebanon. Life is so hard to be here. We need basic rights in schooling, jobs, to be able to move freely

Around 2.1 million Palestinian refugees live in Jordan, of whom 370,000 live in camps where conditions are generally sub-standard. Approximately three quarters of Palestinian refugees in Jordan have been granted Jordanian citizenship, giving them access to health care and education. However, over 600,000 Palestinian refugees have never been naturalized, including some 150,000 who fled to Jordan from the Gaza Strip following the 1967 Israeli-Arab conflict, and as a result do not have sufficient access to public services.

Displaced Once More: Palestinian Refugees from Syria

Palestinian refugees in Syria have been severely affected by the ongoing armed conflict and limited access of humanitarian organizations. According to UNRWA, almost all of the 560,000 Palestinian refugees inside Syria require humanitarian assistance. Of these, some 120,000 have fled to neighboring countries, including Lebanon and Jordan – both of which have imposed tight restrictions on their entry – and to Europe.

Nearly ten thousand PRS have fled to Jordan since 2011. UNRWA estimates that the majority of them live in poverty and with irregular status. There are approximately 32,000 Palestinian refugees from Syria living in Lebanon; almost 90 percent live under the poverty line and 95 percent are “food insecure.” In Jordan and Lebanon, UNRWA provides healthcare, education, and cash assistance to cover the basic needs of Palestinian refugees from Syria. Aside from exceptional cases, Palestinian refugees from Syria in Jordan and Lebanon are generally not resettled to third countries.

The majority of those who have remained in Syria have been displaced multiple times and are disproportionately affected by the conflict, due to their proximity to conflict areas inside Syria and high rates of poverty.

In 2018, the US administration eliminated funding for UNRWA. This draconian action by the current US administration severely threatens the agency’s ability to provide assistance to Palestinian refugees. Since 2008, the USA has on average contributed more than $277 million yearly to UNRWA, a quarter of the agency’s budget. Even with stop-gap funding from other donors, UNRWA has been forced to cut back on basic services. Future funding that originally offset some of the USA’s funding cuts is not guaranteed to continue, with devastating implications for UNRWA’s ability to provide resources to meet basic needs and services such as food and shelter assistance, health care, and education.

Palestinian refugees Amnesty International interviewed consistently reported that UNRWA support is the difference between surviving and having nothing. Humanitarian assistance provided by UNRWA was the only way they could meet basic needs – shelter, food, heat and electricity, medical care, schooling for children. With limited opportunities to work and without assistance and access to UNRWA services, options for finding adequate shelter and food for their families, let alone schooling and medical care, are extremely limited.

Amnesty International is gravely concerned that the current US administration’s decision to eliminate funding for UNRWA is prioritizing political interests over the urgent humanitarian needs and human rights of Palestinian women, men, and children.

Fear of Anti-muslim and Anti-refugee sentiments in the USA

Another subtle change is how the USA is perceived: refugees in Jordan and Lebanon awaiting resettlement to the USA still want to come, but they are aware of anti-refugee, anti-Muslim sentiment in US government policies and are apprehensive about how they will be affected. During stakeholder roundtables between resettlement professionals and refugees and cultural orientation classes, multi-day trainings to prepare refugees for their new life in the United States, refugees are asking more often about how they will be received: "Will we be discriminated against in the USA?" "Is there a ban against Muslims or against Arabs?" "Can we be deported from the USA?" "Can I wear a hijab?”

The longer refugees wait, the greater the human toll and the greater their vulnerability in host countries. As thousands fewer refugees depart each year, aid agencies and national governments require additional assistance; without it, they need to spread similar levels of funding over larger populations, leading to assistance being cut after a period of time. Because of resource constraints, in part generated by protracted refugee situations and also funding remain constant or declining, the UN has had to make painful decisions on who receives assistance in the first instance or continues to receive aid. Refugees reported to Amnesty International that UNHCR stopped their assistance to help other refugees who had not yet received aid, or they had received assistance for a few months only, despite living in Jordan or Lebanon for years. This has led to refugees, with increasingly desperate needs, receiving limited or no assistance.

Lebanon

For refugees in Lebanon who cannot return home or be resettled, the situation is tenuous. On 31 October 2014, Lebanon effectively closed its borders to refugees from Syria. Six months later, UNCHR stopped registration of Syrian refugees at the request of the Lebanese government. Syrian refugees continued to arrive, but were unable to register with UNHCR. The government estimates there are 1.5 million Syrian refugees in Lebanon, including 976,002 registered with UNHCR. There are also some 20,000 refugees of Iraqi, Sudanese, Ethiopian, and other nationalities.

The Lebanese government has stated that refugees cannot become permanent residents – that is, one of the three durable solutions open to refugees – local integration – is not available. Because refugees in Lebanon cannot integrate, they need to maintain residency permits. However, refugees encounter steep financial and administrative difficulties in obtaining or renewing residency permits from the Lebanese government, exposing them to a constant risk of arbitrary arrest, detention, and forcible return to their home countries as well as restricting their access to work, education, and health care.

Due to Lebanese policy, there are no refugee camps administered by UNHCR in Lebanon. Rather, refugees live in cities, villages, or informal tented settlements throughout the country. Some Syrian refugees who are not Palestinian have moved into Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon, which has increased overcrowding and worsened conditions.

According to UNHCR, 76 percent of Syrian refugee households lived below the poverty line and more than half lived in substandard conditions in overcrowded buildings and densely populated neighborhoods. Syrian refugees “have limited possibilities to become self-reliant and are still largely dependent on humanitarian assistance to meet their basic needs and stay resilient against exploitation, evictions and other risks.”

Jordan

Similarly, refugees in Jordan face an increasingly difficult situation. Jordanian authorities began tightening border controls with Syria in 2012 and closed its borders to Syria’s refugees in 2014, with some limited exceptions. Jordan hosts 762,420 refugees: 671,579 are Syrian, while 67,600 are Iraqi; and some 23,241 are Yemeni, Sudanese, Somali, and other nationalities.

Refugees in Jordan face significant challenges in supporting themselves and accessing services. UNHCR reports refugees “have entered a cycle of asset depletion, with savings exhausted and levels of debt increasing.” In 2018, the Jordanian government raised the cost of public health care services for Syrian refugees, putting basic care beyond the reach of most, as over 85 percent of Syrian refugees live below the poverty line. Eighty-four percent of all refugees in Jordan live in urban areas, while approximately 16 percent of Syrian refugees live in one of three UNHCR camps.

Like Lebanon, Jordan has not signed the 1951 Refugee Convention or its 1967 Protocol, but remains bound by customary international law and by other international human rights instruments that apply to refugees and non-refugees alike. However, there is a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) between UNHCR and the Jordanian government on refugee protection operations.

Amnesty International visited the Zaatari and Azraq camps, which house only Syrian refugees. In coordination with UNHCR and the Jordanian government, multiple NGOs provide a range of services and programs for refugees, such as schooling, health care, skills development, arts programming, and sports. In Zaatari, there is a crowded unpaved main street filled with stalls selling household goods, clothes, appliances, and food. In Azraq, there is a square of such stalls selling similar goods and food. Yet, refugees living in the camps reported to Amnesty International a sense of confinement and limited opportunity. Their lives are on hold.

We feel restricted in every way. We are restricted when we go out, we are restricted when we come back.

Located near the city of Mafraq, Zaatari is a walled-off dusty compound holding some 80,000 refugees with heavy security to enter and leave. It has the feel of a bustling small town, albeit one ringed by walls and patrolled by security and intelligence authorities from the national government. The Azraq refugee camp, home to approximately 40,000 refugees, looks and feels like a military compound, with quadrants of shelters set up in a grid system. There is nothing for miles around the camp except barren landscape. On the approach to Azraq, a city of white tents appear on the horizon, looking like an outpost for a military installation.

For refugees in these camps, this is the extent of their world. Once they enter, they cannot leave – unless they choose to return home, even if the reason for their persecution and flight still exists, or they are resettled. Freedom of movement is highly restricted. Refugees need permission to leave a camp, and refugees who are found outside a camp without the correct papers are returned to the camp and in some cases deported.

These camps are not residential spaces. They feel like prisons, surrounded by walls with concertina wire at the top.

Even as refugees try to make a “home” in an impossible situation, they cannot escape the literal and figurative barriers keeping them there. These camps are not places for homes; they are a place of containment.

I don’t have a life here. It is reduced to watching TV. I am dying here.

A generation of children is growing up there.

Refugee Resettlement: A Vanishing Lifeline

Unable to return home, the majority of refugees stay in their host country where they try to build a new life, but for a small minority with specific protection risks staying in their initial host country is not an option and resettlement is necessary.

Resettlement is the relocation of “vulnerable” refugees from countries where they have initially fled to safe third countries where they can restart their lives in dignity. Resettlement benefits refugees who are facing particular hardships or vulnerabilities. Resettlement also relieves some of the pressure on countries hosting large numbers of refugees.

UNHCR initially identifies vulnerable refugees for resettlement according to set criteria. Those with serious medical needs, survivors of torture/violence, women and girls at risk, children and adolescents at risk and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) people are among some of those prioritized for resettlement. Once refugees have been identified by UNHCR, their cases are put forward to resettlement countries which then decide whether to accept them for resettlement. If accepted, these governments actively facilitate the safe transport of refugees to their country and help them to integrate into their new countries.

In addition to UNHCR-coordinated resettlement, Amnesty International encourages other means of relocating refugees safely including through other admission pathways, such as humanitarian admission programs, family reunification, and sponsorship programs so long as they guarantee the rights of refugees.

Fewer than one percent of the world's refugees will have the opportunity to resettle in a third country like the United States. Refugees do not get to choose to resettle to the USA or any specific country. A refugee is only admitted to the USA after referral to the US resettlement program by UNHCR and then undergoing extensive security checks and being found eligible for admission under US immigration laws.

Resettlement is a lifeline for refugees with specific protection risks, and the USA has historically resettled the largest number of refugees annually from around the world. Since the USRAP was established by the 1980 Refugee Act, and until 2017, US administrations have, on average, set the ceiling for refugee resettlement to the USA at 95,000. Annual admissions to the USA have averaged 80,000 refugees.

We came to Jordan in 2013. The revolution started [in Syria] in 2011, so we lived for three years there under bombing, war pressure, checkpoints, and kidnapping. We faced lots of tragedies there but we weren’t thinking about leaving despite all of that. But at the end we didn’t have another choice. There was no way: either we die or we leave . . . we didn’t have another choice or solution.

Under the current US administration, that lifeline has been strangled, with grave implications for resettlement to the USA and worldwide. Since January 2017, a series of Muslim and refugee bans, various policies imposing additional security screening measures, and drastic cuts to the annual ceiling for refugee admissions have made the US refugee program a shadow of what it was only a few year ago.

Within a week of taking office, President Trump reversed nearly 40 years of US support for refugee protection through a single discriminatory act with catastrophic consequences. On 27 January 2017, he signed the Muslim ban, which suspended the USRAP for 120 days and imposed an indefinite ban on the resettlement of refugees from Syria, among other provisions. A revised executive order took effect in March 2017, which lifted the indefinite ban on Syrian refugees but still suspended the US refugee resettlement program. A June 2017 ruling by the US Supreme Court allowed a limited version of the March executive order to take effect.

Refugees whom Amnesty International interviewed continue to live out the consequences today of the Muslim ban. Their cases were put on hold after this initial Muslim ban and 2.5 years later, they are still awaiting resettlement to the USA.

Nine months into his presidency, Trump continued to systematically rollback US systems for refugee protection. On 24 October 2017, even as President Trump signed an executive order to resume the USRAP “with enhanced vetting procedures,” he also imposed an additional 90-day ban on refugees from 11 countries while ordering that changes to security vetting procedures be applied retroactively. Nine of the 11 countries in the new refugee ban were Muslim-majority, and accounted for 43 percent of US refugee admissions for the previous fiscal year, 2017. In January 2018, the US administration issued a memorandum ordering additional security procedures for refugees from the 11 countries designated in the October 2017 executive order. These successive discriminatory executive orders and memorandum set in motion long-term and negative consequences for refugee resettlement, disproportionally affecting refugees from Muslim-majority countries.

We would like to thank the American people for standing by the Syrian people. They wanted to help the Syrian people in a better way, but all of a sudden, the support stopped. We don’t know what the reason is. I mean, America is the country of freedom. The country that doesn't oppress people

The current US administration has further dismantled refugee protection by drastically limiting refugee admissions in the yearly Presidential Determination, which designates the annual number of refugees to be resettled to the USA. One of President Trump’s first acts in office was to cut refugee admissions from 110,000 for FY 2017, as set under President Obama in his last year in office, to 50,000. For FY 2018, President Trump lowered the ceiling to 45,000, breaking precedent. It was the lowest refugee admissions ever set. Compounding this harm, the USA then barely resettled 22,000 refugees – the lowest number admitted through the USRAP in the history of the program.

The downward spiral continues: the ceiling for refugee resettlement in FY 2019 is 30,000 – setting a new record for the lowest ceiling for refugee admissions since the US refugee program started in 1980. As of May 2019, the USA is on pace to resettle fewer than 25,000 refugees for the current fiscal year. Similarly, it is not on pace to reach the 9,000 allocation for refugee admissions for countries under the category of “Near East/South Asia.” In contrast, in FY 2016, the USA resettled nearly 85,000 refugees.

The USA has turned its back on refugees – and renounced its commitments to share responsibility for hosting refugees. The bare math of refugee resettlement tells the story. Under the current US administration, refugee resettlement dropped 71 percent in three years. President Trump has decimated the USA’s global leadership on resettlement, not only by cutting refugee admissions to the USA, but also exemplified by the dramatic renunciation of US policy commitments in President Obama’s Leaders’ Summit in 2016 and the global compacts on refugees and migrants.

US policies have undermined the international refugee protection system itself. The decline in global resettlement since 2017 – despite the urgent and consistent need – is due in large part to policies enacted by the current US administration. The number of refugees resettled worldwide dropped nearly 50 percent from 2016 to 2017. During that same period, the USA resettled 65 percent fewer refugees.

As the USA has cut its refugee admissions and enacted discriminatory refugee policies, starting with the Muslim ban, fewer refugees have simply been resettled worldwide because the US has shut its doors and other countries have not filled the gap. This failure is due partly to other countries’ inability to offer a larger number of resettlement slots because they do not have the same infrastructure for processing refugee admissions. The US refugee program was, as Amnesty International was told, built for size. It is also because the USA’s policies have emboldened other countries to adopt similarly restrictive policies that undermine responsibility-sharing, including limiting resettlement, and create unwelcoming environments for refugees.

Once a leader in resettlement, since 2017 the USA has the cut the number of refugees it admits more than any other resettling country. In 2016, the USA resettled 62 percent of all refugees referred by UNHCR. In 2017, this number dropped to 38 percent. In 2018, the USA was resettling only half of the number of the world’s refugees that it once did – it resettled only 31 percent of all refuges referred by UNHCR. As of the end of April 2019, USA had resettled only 38 percent of all refugees referred by UNHCR for resettlement around the world. While this number indicates the USA is on pace this calendar year to resettle slightly more refugees of all those referred by UNHCR, the USA still resettles around half as many refugees that the UNHCR refers for resettlement globally as it once did.

The shocking reduction in resettlement of refugees from Muslim-majority countries since the Muslim ban has further eroded refugee protection.

Since FY 2016, resettlement to the USA of refugees from Muslim-majority countries listed in the Muslim ban and other executive orders has dropped 98 percent as of June 2019. To put a finer lens on it, even as 42 percent of the world’s refugees requiring resettlement are from Syria, only 347 Syrians have been resettled to the USA through May in FY 2019. In contrast, at this same point in FY 2016, the USA had resettled 2,805 Syrians. By the end of FY 2016, the USA had resettled 12,587 Syrians, whereas the USA is on pace to resettle just over 500 Syrian refugees in total in FY 2019. Similarly, 282 Iraqis have been resettled through May in FY 2019 as compared to 5,380 resettled at the same point in FY 2016. By the end of FY 2016, the USA had resettled a total of 9,880 Iraqi refugees, but is on pace to only resettle just over 400 Iraqis in FY 2019.

A SHADOW OF ITSELF

The US refugee program is now a shadow of itself. In multiple interviews, Amnesty International was told how processes that could be done in several weeks now take a year or longer due to changes in vetting. Because of changes to the security vetting process, it is a challenge at best to estimate how long it will take someone to move through the refugee resettlement pipeline. Not only are more human resources needed, the process also needs to be faster. Changes implemented to purportedly improve the system have harmed it instead. This has resulted in significant processing delays and a continued inability to meet the annual refugee admissions ceiling set by the Presidential Determination.

Amnesty International also observed the toll taken on refugee protection professionals working with refugees. Amnesty International was told of the types of impossible decisions facing them: whether a 63-year-old man with end-stage cancer or a 13-year-old with a medical need should be put forward first for resettlement, knowing that the elderly man not live until the security processing is completed, even for an expedited case, due to the backlog. Cases simply do not move quickly. This, coupled with the inability to provide answers to those waiting beyond a general statement that their case in “security checks,” have resulted in deep stress to employees seeking to fulfill their mission.

Through successive and discriminatory policies restricting refugee resettlement to the USA, the current US administration is failing to share responsibility for refugee protection. According to the principle of responsibility sharing and international cooperation, the USA, like all countries, should do its fair share to support refugee protection through resettling refugees. But it is not. When the USA abrogates its responsibilities, not only does it harm individual lives in grave danger who might have been resettled to the USA, it also shrinks the protection space for refugees worldwide.

Refugees in Jordan and Lebanon: ‘Just Give Us Hope’

In Jordan and Lebanon, the impact of the USA cutting its resettlement commitments has had an acute impact on the international protection system and on refugees themselves. People feel hopeless, and US policies have contributed to that.

Due to the current US administration’s targeting of refugees from Muslim-majority countries and the high concentration of refugees from some of these countries in Jordan and Lebanon, resettlement out of Jordan and Lebanon has been decimated. UNHCR reports that resettlement out of Jordan dropped by more than four-fold from 2016 to 2017, “primarily due to the change in the US resettlement policy at the beginning of 2017.” It anticipates that in 2019, resettlement from Jordan will remain around the 2017 levels. While the effect of US policies on Lebanon has not been as marked, it has contributed to the drawing down: resettlement out of Lebanon has dropped 89 percent since 2016.

In 2016, more than 11,500 refugees were resettled from Jordan to the USA alone, out of a total of 19,303. In 2017, the USA resettled 1,374 refugees from Jordan – only 12 percent of its commitment in 2016. In 2018, the USA admitted 19 refugees from Jordan out of the 5,100 total who were resettled worldwide from the country. In Lebanon in 2016, 19,502 refugees were resettled worldwide, of whom the USA resettled 1,072 – 5 percent of all refugees from Lebanon. In 2017, the USA resettled only 400 refugees from Lebanon, out of 12,617 resettled worldwide – less than one percent. In 2018, the USA resettled merely 27 refugees out of 9,805 refugees resettled from Lebanon worldwide.

The numbers in this instance tell a shocking story – of the shuttering of USA resettlement from Jordan and Lebanon. The top two nationalities resettled from both countries to the USA are Syrian and Iraqi. According to UNHCR, in calendar year 2016, more than 11,500 refugees were resettled from Jordan to the USA alone, out of a total of 19,303. In calendar year 2017, the USA resettled 1,374 refugees from Jordan – only 12 percent of its commitment in 2016. In calendar year 2018, the USA admitted 19 refugees from Jordan out of the 5,106 total who were resettled worldwide from the country. In Lebanon in 2016, 19,502 refugees were resettled worldwide, of whom the USA resettled 1,072 – 5 percent of all refugees from Lebanon. In 2017, the USA resettled only 400 refugees from Lebanon, out of 12,617 resettled worldwide – only 37 percent of its commitment in 2016. In calendar year 2018, the USA resettled merely 27 refugees out of 9,805 refugees resettled from Lebanon worldwide.

Reshaping the Resettlement Landscape

These cuts to resettlement are causing immeasurable stress and changing the course of lives of refugees. Refugee protection professionals in Jordan and Lebanon described to Amnesty International how refugees are searching for any piece of information to understand why they are still waiting for an answer on their case after years. When refugees inquire about cases, they say, “just give us hope.”

Refugees have been forced to put their lives on hold. Refugee protection professionals and service providers in Jordan and Lebanon told Amnesty International that refugees are holding off having children or getting married for fear of further delaying the processing of their resettlement case after years of waiting. The fear is not unfounded. The birth of a newborn, for example, requires new paperwork during which time medical and security clearances can lapse, pushing a refugee’s case further back in an already long pipeline.

Case Studies: Refugee Voices from Jordan and Lebanon

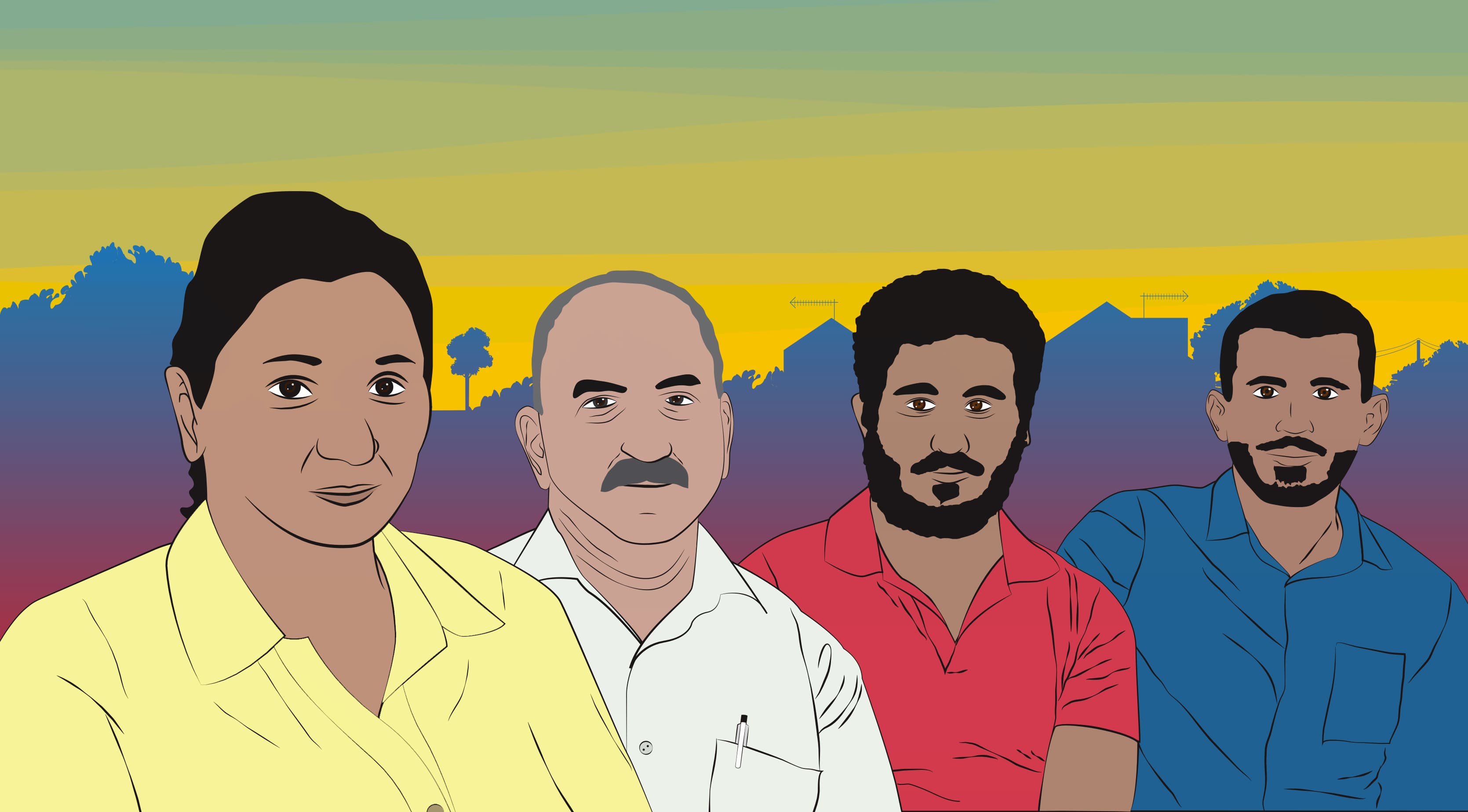

”Refugee” is only a temporary term; it does not reflect the whole identity of a woman, man, and child who has left their home in search of safety. A person’s legal status as refugee cannot express their full identity and personality.

In multiple interviews, people shared with Amnesty International stories of their lives before they were forced to flee their homes, their hopes for their children and their own future, and how now their lives were on hold – they cannot return home, they cannot plan for an unknown future, and for those awaiting resettlement, the promise of safety in the USA remains illusory. Of the parents with whom Amnesty International spoke, their biggest hope is for their children to be educated. Adults want to work to be able to support themselves and their families, but jobs are scarce even as UNHCR aid is cut.

Syrian refugees interviewed by Amnesty International wonder why the USA has stopped resettling them. Like any person, they miss their home but many feel they can never go back because they would be at risk of harm by Syrian authorities. Others would like to return one day but cannot see returning for the foreseeable future because of the continuing armed conflict and other human rights threats, like forced conscription and enforced disappearances.

The mountain is in front of us and the sea is behind us.

Following are some of their stories. Their accounts show the harm of US policies on refugee protection in host countries, the shared concerns of people everywhere for safety, education, employment to support themselves and be productive, and people seeking lives with dignity and hope no matter their circumstances.

‘We want to live; we want to live in peace’

Malik, refugee in Beirut, Lebanon

Fearing for their lives on account of their Christian faith, Malik, 65, fled Baghdad, Iraq, to Beirut, Lebanon, with his wife and two sons in 2013. Three years later they were accepted for resettlement to the United States. As proof of his place in the resettlement process, Malik proudly showed Amnesty International his cultural orientation certificate, which indicated that he and his family had participated in a multi-day training to prepare them for their new life in the United States.

Malik and his family were awaiting the final step of the resettlement process after cultural orientation – being told to pack their bags for a flight to their new home – when the Muslim ban was signed in January 2017. Malik does not know when, if ever, his case will be resolved. He is told only that his case is on hold for “security checks,” a confusing explanation as his case was once approved.

This perpetual sense of limbo in which he and his family have been placed by the US government is taking a psychological toll. Malik told Amnesty International: " We are suffering. We are suffering a lot. Quite frankly, we used to have a problem every day in the house, especially my wife. The kids would say, ‘What can we do, mother? It's out of our control. It's something that's out of our control . . . I used to comfort her too . . . But every day she would say, ‘Why us? What did we do? We are good people. We love people. We don't hurt anyone. We've never, in our lives, hurt any person.’ "

Like most refugees in Lebanon, Malik and his family do not have residency permits, putting them at risk for arrest, detention, and even deportation, even though they are registered with UNHCR and are awaiting resettlement to the USA.

Malik had greeted Amnesty International with, “I welcome you, but I wish I would've met with an organization like yours two years ago or with [other] people who defend our rights. We don't know who to go to, that's why I want to thank you, because I've already completed my paperwork and I'm only waiting for a visa.”

When asked what he would say if he could speak with President Trump, Malik said, “We are refugees. We're human refugees. We're refugees because there are difficult situations that made us flee . . . Please, so that we're able to live. ”We want to live; we want to live in peace.” – Malik, refugee in Beirut, Lebanon

'It is our only hope'

Ahmed, refugee in Beirut, Lebanon

In late December 2016, Amina* and Ahmed* were told to buy luggage and prepare to move to the United States. They had been approved for resettlement to the United States and informed their new home would be in Richmond, Virginia. They gave away the belongings they could not bring and their excitement grew. They had fled Aleppo, Syria, in 2013, and now they finally were going to be resettled. Ahmed told Amnesty International, “We felt at the time this was our new home.”

When President Trump signed the Muslim ban in January 2017, Ahmed and his family were shocked. He was told to wait until the ban was over and then his case would proceed. Since that time, his family’s case has been stuck in processing. He has no sense of when his family will be able to travel to the USA.

Two-and-a-half years after expecting to begin a new life in Richmond, Virginia, Amina and Ahmed and their four children are still waiting, in an increasingly desperate situation. Ahmed will soon lose his residency status, exposing him and his family to the risk of arbitrary arrest, detention, and forcible return to Syria. The carpet store where he works is closing in a few months. He is looking for a job but without a residency permit, he is not sure how he will find a new one and support his family. UNHCR had provided them limited financial support, but he was told by UNHCR that it was discontinued due to budgetary shortfalls.

“It is really hard, really difficult [living in limbo in Lebanon],” Amina and Ahmed told Amnesty International. They cannot return to Syria because of the war. Ahmed is fearful of forcible conscription by the Syrian military, and believes that returning would endanger his family’s life due to the ongoing armed conflict, which forced them to flee originally.

Just as they cannot return home, they cannot move forward in their resettlement to the USA. When Ahmed calls about the status of their case, he is told that it is in security checks. Ahmed told Amnesty International, “Every time the phone rings, we think it will be positive news. It is our only hope.”

Ahmed and Amina were excited to go to the USA because there, people have rights and “children can go to school.” Their eldest daughter, Hasna*, wants to be a designer when she grows up, and their second daughter, Mayiran*, a surgeon. Their third daughter, Raja*, wants to be an orthopedist. Their son, Amir*, wants to be a doctor.

With tears in his eyes, Ahmed told Amnesty International that if he could speak to President Trump, he would tell him that that they come in peace. They are the victims and are looking for security and safety. They are asking for his help.

'We are hoping that the countries would support us through resettlement'

Fatima, refugee in the Azraq Refugee Camp, Jordan

In Dara’a, Syria, Fatima* was an English teacher, and her husband worked at an electricity company. In 2013, a plane destroyed their home. Her husband left for Jordan first, and shortly after, she followed with their son. Today they live in Azraq refugee camp.

Until October 2018, Fatima facilitated operations for teachers at an international NGO in the camp. Due to funding cuts to the NGO, she lost her job. Now, she teaches her son and her neighbor’s daughters during the day. Her son likes math and wants to become an engineer. Fatima would like to run a small school for students with learning challenges, or work within a larger school to help address the special needs of children there.

Fatima says that UNHCR funding cuts have impacted people living in Azraq camp. Before, she says, people used to be able to buy clothing and afford medicine. That’s no longer true. The food vouchers, equivalent to 20 JOD per month, per person, are not enough.

Fatima knows she cannot return to Syria, where her home was destroyed and there is no peace. All of the people who go back, she says, are arrested or killed. Fatima hopes to be resettled to the USA one day and does not understand why the USA stopped helping:

" I mean, this is our voice through you, the voice of all Syrian refugees in Jordan. We are asking for your help. We are hoping that the countries would support us through resettlement. We have qualified professionals, qualified educators, skilled people who are self-sufficient."

'I just hope they show compassion to me and my children'

Nadia, refugee in Beirut, Lebanon

Before fleeing to Lebanon, Nadia* lived for 10 years in the port city of Latakia with her six children and their father. They left Syria after the war began in 2011 and registered with UNHCR shortly after. The children’s father sold cigarettes and coffee to support them, but left the family some time ago.

Today, Nadia and her children live in the Ain Al-Hilweh camp in Lebanon, a Palestinian camp where many Syrians also live, because it is cheaper. She and her six children share a small structure with one room for the children, one room for her, a kitchen, and a bathroom. Her “zinco” roof has been leaking for two months, and the blankets and linen are always wet.

Arafat*, her son, was shot in the head in Lebanon in 2017 while he was on his way to buy kanafeh, a traditional Levantine dessert. He was caught in the cross-fire between rival armed factions. He now suffers from epilepsy , and Nadia says he is not always able to get the treatment he needs for the brain damage he suffered. “They’re doing everything they can, but his condition is terrible. He has no life.” At the camp, he is taunted by others who call him derogatory names because of his medical condition; people start fights with him, and push him into walls. The day before Nadia interviewed with Amnesty International, she was struck in the face when she interrupted a group of people who were hitting her son.

The thought of returning to Syria does not even cross her mind. It is impossible. She is afraid to return, and photos and news reports do not capture what she and her family have experienced. She wants to leave Lebanon for her children’s benefit. Her six-year-old daughter recently told her, “I want to die.”

Of herself she just says, “I’m tired.” Nadia doesn’t have child care assistance because she cannot afford it. When she speaks to people in Lebanon, they insult her, and tell her that Syrians should get out of their country. At one point during the interview, Arafat told his mother not to cry and hugged her, beginning to cry himself. After spending a few moments hugging him, she pushed Arafat away, assuring him, “I’m not crying.”

Nadia says she would like to go to any country, anywhere else: “I just hope they show compassion to me and my children.”

'I want [my children] to be like other people, like the other youth'

Sania, refugee in Zaatari Refugee Camp, Jordan

Sania*, a Syrian refugee, lives at Zaatari refugee camp with her three children, Ali*, Fauzia*, and Sameer*. The family fled Dara’a in 2012 because of the war. Sania’s husband left the family, remarried, and moved back to Syria. Sania is grateful for her life at Zaatari, where “no one hits or shoots me and my kids.” She cannot envision returning to Syria.

She receives vouchers from UNHCR worth 80 JOD per month. Because it’s not enough to support the family, she sometimes uses them to buy goods, which she then re-sells for a higher price. Without the 80 JOD per month, she and her children would not be able to live. Even if she were authorized to work, she would be unable to because two of her children have disabilities and no school will accept them. She must stay home to take care of them. She’s been told they need to go to a “special school” where their needs will be met. Sania herself requires medical care for back pain that is becoming debilitating.

“I want my kids to receive treatment and I want them cured from their conditions. I want them to be like other people, like the other youth. I ask God to give me strength to be able to provide for them. That’s my wish. I ask the Lord of worlds to give me strength for them. And I pray to God and ask him to heal them.”

Sameer says he likes school because he gets meals there. He likes bananas, apples, and sandwiches best. He wants to be a teacher one day. Ali wants to grow up to be a man and take care of his mother, and Fauzia wants to grow up to be a lady and to play with other girls.

'They have dreams'

Zainab, refugee in Beirut, Lebanon

Zainab* and her three children, Farah*, Basma*, and Hamza*, are originally from Suweida in Syria. Zainab farmed in Soweda, and her children attended school. In early winter 2012, as they fled by car to escape shelling, their vehicle was hit by shrapnel. It erupted in flames, and they escaped only thanks to onlookers who pried them out of their car. The family was very badly burned, and they thought they would die while waiting hours for care at a hospital.

For six years, they moved around Syria in search of safety and medical care, but in 2018 fled for Lebanon. In November, they started receiving assistance for rent and food from UNHCR.

When they first came to Lebanon, life was hard. Sometimes they only had one meal a day because they couldn’t afford food. Other times, people would share their food with them to help. They want to work, but when people see their burned hands, they won’t hire them. Zainab says, “We can work with our hands but people think otherwise.”

Her children do not go to school and spend their days at home because of their injuries. Zainab is afraid that they will be mistreated because of their burn scars, and that this will have hurt them psychologically. Her children do not let their injuries deter them. “They have dreams,” she says. Farah would like to be a school teacher or lawyer, and Basma a drawing teacher. Hamza, the youngest, likes computers.

Conclusion

The USA’s retrenchment in refugee protection has had profound global effects. For the first time since the US refugee program began in 1980, the USA is no longer the global leader in refugee resettlement.

This has been a deliberate choice by the current US administration, executed through a series of discriminatory policies disproportionately affecting refugees from Muslim-majority countries and other policy decisions slashing refugee admissions and adding extreme vetting processes. Other countries have not filled the gap created by the precipitous drop in refugee resettlement, in part emboldened by the USA’s discriminatory and restrictive policies. Global resettlement dropped 84 percent from calendar year 2016 through 2019. Behind every number is a face, a name, a person who has experienced deep loss and who hopes for a better future.

During its two-week mission to Jordan and Lebanon, Amnesty International documented firsthand these profound impacts – from the refugees themselves living out the consequences of the US’ discriminatory and restrictive policies. In multiple interviews in Jordan and Lebanon, men, women, and children spoke of lives in limbo. Universally, all said they could not go home for fear for their security and lives. Refugees above all expressed the same desire any person in their situation would have: the desire to live with dignity, provide for their families, and have a sense of purpose and clarity about their situation and future. Palestinian refugees universally told Amnesty International how UNRWA’s assistance was the critical difference between a subsistence life and having nothing.

The catastrophic reach of the Muslim ban continues. Consistently, refugees expressed disbelief that the USA could not resettle them as promised, and bewilderment and even pain at the USA’s abrupt change toward supporting and welcoming refugees. Amnesty International met with refugees who, two-and-half years later, are still in the resettlement pipeline to the USA. They continue to await an answer on their cases, and for those on the cusp of being resettled in early 2017, are still waiting for the USA to make good on its promise to resettle them to their new homes. They carry with them forever the knowledge, in their words, they were “banned.”

People working directly with refugees described how the current US administration’s policies have distorted a once well-functioning refugee protection program, rendering it a shadow of itself. US policies have shifted the resettlement landscape, doubly impacting some of the most vulnerable refugees and creating other harm in untold ways. These abrupt policy shifts have produced incredible stress for people working to support and assist refugees, let alone refugee men, women, and children already in difficult situations.

Amnesty International urges the USA to reverse its discriminatory and restrictive policies on refugee protection and uphold its commitments to share responsibility for refugee protection. The USA should ensure it admits the number of refugees set for resettlement in the Presidential Determination for FY 2019, and commit to resettling at least 95,000 refugees in the next Presidential Determination. US authorities should revise policies that hinder resettlement of refugees to ensure processing is timely and all refugees are considered fairly and fully for resettlement to the USA, without discrimination. The USA should further provide robust, sustained funding for humanitarian aid to protect displaced populations around the world, including for Palestinian refugees, and provide robust funding and support for the US refugee program.

Key Recommendations

To the US President and relevant federal agencies

- Admit 30,000 refugees as set in the Presidential Determination on Refugee Admissions for Fiscal Year 2019

- Ensure that each regional allocation as set in the Presidential Determination for Fiscal Year 2019 is met, including the regional allocation of 9,000 refugee admissions for the “Near East/South Asia” region. If the regional allocation is unable to be met, a clear justification should be provided to the US Congress on what steps were taken to meet the regional allocation, and what steps have been taken to ensure the overall refugee admissions goal is met

- Set the Presidential Determination for Fiscal Year 2020 to admit at least 95,000 refugees

- Reverse policies and procedures limiting refugee resettlement, including those that disproportionately impact refugees from Muslim-majority countries and unnecessarily prolong and delay resettlement processing

- Apply the provisions of the 1951 Refugee Convention and the 1967 Protocol to refugees without discrimination

- Restore in full critically needed funding for UNRWA at levels consistent with the US’s historical contributions

To the US Congress

- Hold the US Presidential Administration and relevant federal agencies accountable to admitting 30,000 refugees set in the Fiscal Year 2019 Presidential Determination, including ensuring each regional allocation is met

- Call on the US Presidential Administration and relevant federal agencies to set the Fiscal Year 2020 Presidential Determination to admit at least 95,000 refugees, and conduct vigorous oversight to ensure the US administration works to achieve the goal it set

- Appropriate robust funding for the US Department of Health and Human Services’ Refugee and Entrant Assistance account; the US Department of State's Migration and Refugee Assistance account and Emergency Refugee and Migration Assistance account; and the US Agency for International Development’s (USAID) International Disaster Assistance account to provide life-saving and life-preserving international assistance for refugee and displaced populations around the world

- Appropriate robust funding to ensure the US Refugee Admissions Program is provided the resources needed to resettle the amount of refugees expected each Fiscal Year

- Further strengthen and make explicit policies of non-discrimination protections in both US refugee and asylum systems

- Co-sponsor and pass the National Origin-Based Antidiscrimination for Nonimmigrants Act, otherwise known as the NO BAN Act (H.R. 2214/S. 1123), which would amend the Immigration and Nationality Act to explicitly prohibit discrimination based on religion

- Co-sponsor and pass the Guaranteed Refugee Admission Ceiling Enhancement Act, otherwise known as the GRACE Act (H.R. 2146/S. 1088)

- Appropriate funding to restore humanitarian assistance to UNRWA at levels consistent with the US’ historical contributions